In our above example we have a number of terms that potentially refer to the same entity (see highlights).

This note provides some guidance on how to capture requirements using the ReqSpec notation and AADL, and to make requirements verifiable through analysis of AADL models through the Architecture-Led Incremental System Assurance (ALISA) capability that is now part of OSATE. For more detailed documentation we refer the user to the online help for ALISA in OSATE and the ReqSpec Technical Report.

An example model called SimpleControlSystem used in this guidance is available at Github.com/osate/alisa-examples.

The guidance approach is as follows. Elicitation of stakeholder requirements focuses on capturing the goals and desires of stakeholders. These requirements, which we refer to as stakeholder goals, should be traceable to specific stakeholders, may be refined into sub goals, they may evolve, and they may be in conflict with each other.

In a separate phase we develop system requirements. They are derived from the stakeholder goals. System requirements become the contract that must be met by a system implementation, i.e., must be verifiable or satisfiable. Verification plans specify the verification activities necessary to show that a set of requirements are met.

ReqSpec allows goals and requirements to be organized in a document structure with sections and subsections, or into goal/requirement sets aligned with systems and subsystems expressed in an AADL model.

In this guidance we recommend that stakeholder goals be organized in a document structure, which is a familiar format and does not require the creation of an AADL model. This allows the focus of stakeholder goal elicitation to be on capturing the information provided by the stakeholders. We recommend that in a second phase system requirements be organized around an AADL model of the system of interest, its operational context, and as appropriate any subsystems that are identified in the stakeholder goals. In the process ambiguities with respect to the system boundary, the consistency, completeness, and verifiability of requirements are resolved.

We proceed by illustrating each of the two phases.

This is followed by a discussion of how verification plans can be specified and how users can define their own verification methods for verifying requirements.

Stakeholder goals are captured in files with the goaldoc extension. Users create such files with the New .. File command under the File menu.

The content of the file consists of a document with a name and a title string, followed by the document content in square brackets.

The document name acts the qualifier for external references to goals and is assumed to be unique within the OSATE workspace.

The document content consists of a description as a multi-line string, a set of section, and goal. The description is intended as introductory text for the document before the first section or goal.

A section consists of a section name, title string, and its content in square brackets. The content is a description, (sub)sections, and goals.

A goal consists of a name that is unique within the goal document, a title string and its content in square brackets. The goal content is a description and optionally a reference to a stakeholder.

With these three constructs users can create stakeholder goal documents that follow a traditional document structure that organizes goals into sections and subsections.

Goals have unique names within a goal document. They are referenced by their unique name within the same goal document and by qualifying the name with the goal document name if a goal in a different goal document is referenced. The placement of goals in sections does not affect how goals are referenced.

Stakeholder goals can be divided into sub goals. We do this by adding the sub goal as goal and referring to the original goal with refines.

document SCSgoals : "SCS stakeholder goals" [

description "This document contains the stakeholder requirements for the Simple Control System (SCS).

The SCS provides control for a simple device (SD).

The SCS system consists for software, hardware, and physical components."

section SystemFunctionality : "System Functionality" [

goal g1: "Feedback Control"

[ description "The simple controller (SC) shall provide stable feedback control of the SD."

rationale "The SD is a safety critical device that cannot tolerate erratic behavior."

stakeholder sei.phf

]

goal g2: "Digital Feedback Control" [

description "The SCS system shall control the SCS device with a digital controller"

stakeholder sei.phf

]

goal g3: "electrical power"

[ description "The simple control system shall be supplied with 15V electrical power."

stakeholder sei.phf

]

]

section NonfunctionalProperties : "Nonfunctional system requirements"

[

goal ng1 : "Safety" [

description "The system shall be safe"

rationale "This is a control system, whose failure affects lives. "

stakeholder sei.phf sei.dpg

]

goal ng1_1: "Physical damage"[

refines ng1

description "The controller shall not cause the simple device to damage objects in its operational environment"

]

goal ng2 : "Maximum weight" [

description "The system shall stay within a specified weight limit."

stakeholder sei.phf

rationale "The system is part of an aircraft."

]

]

]

We can define stakeholders in a file with the extension org. Stakeholders are placed into an organization. A stakeholder entry has a name and a number of content fields. A stakeholder is referred to in goals by organizationname.stakeholdername.

organization sei

stakeholder phf [

full name "Peter Feiler"

]

stakeholder dpg [

full name "David Gluch"

]

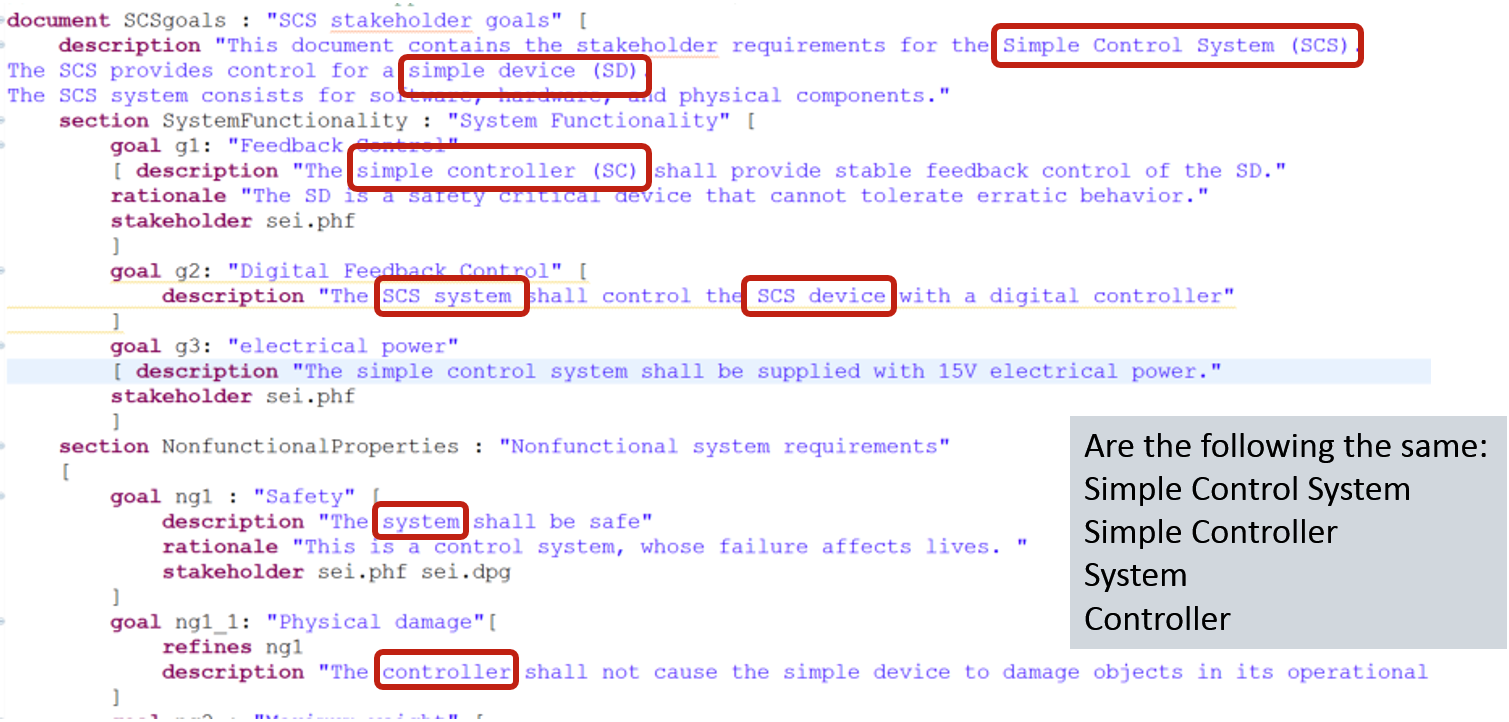

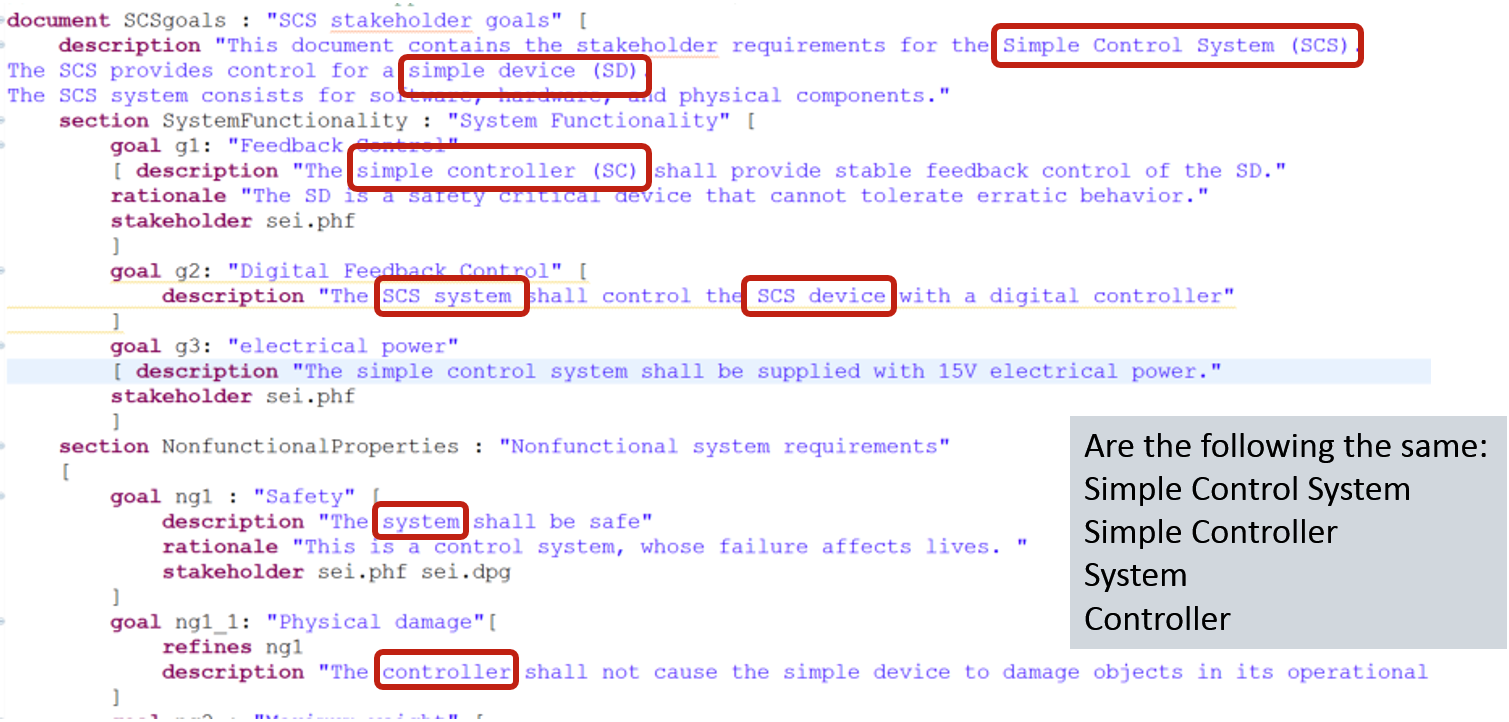

When stakeholder goals are captured the system they apply to may be identified by different names. Figure x illustrates this for our example. Goals sometimes refer to elements in the operational environment or to different parts of a system. When we translate stakeholder goals into system requirements we want to make the requirements verifiable and we want to be clear about the system boundary.

In our above example we have a number of terms that potentially refer to the same entity (see highlights).

When defining system requirements we want to be explicit about the entity we are referring to. We do so by organizing requirements into requirement sets: one set for the system, one for each element in the operational environment, and one for each part within the system. This helps clarify the system boundary, i.e., clearly identifies what the requirement is for.

We do this in two steps. One step is to identify the system of interest by name through a for statement in the requirement set. If the system of interest does not exist as an AADL model element yet, a warning is provided. In a second step we define a system type in an AADL model to represent the system of interest. For elements of the operational environment we may use an abstract type.

We place requirement sets in files with the reqspec extension. A requirement set is declared as system requirements with a globally unique name (dotted name), a title string, a for statement identifying a component classifier, and its content in square brackets. The content is a description of the requirement set and a set of requirement declarations.

Each requirement has a name that is unique within the requirement set, a title string, an optional for statement, and content in square brackets.

The content of a requirement consists of a description, an optional rationale, and an optional traceability link to a stakeholder goal (see goal).

Requirements can be refined into sub-requirements. We do this by adding the subrequirement as requirement and referring to the original requirement with refines. In this case both the original requirement and the refined requirement are associated with the same system.

ReqSpec distinguishes different forms of derived requirements, such as refinement, decomposition into requirements on subcomponents (see below), etc. For more details see ReqSpec Technical Report.

system requirements scsreqs for SimpleControlSystem::SCS [

description "These are requirements for SCS"

requirement R2 : "SCS response time"

[

description "The SCS shall have a response time of 25ms"

rationale "This response time is necessary to maintain stable control behavior."

see goal SCSgoals.g1

]

]

If we want to keep track of different terms that refer to the same entity, we can make use of a user defined property that lets us associate multiple names with an AADL model element. An example definition is shown here.

property set ACVIP is

Aliases: list of aadlstring applies to (all);

Author: aadlstring applies to (all);

end ACVIP;

The property is then used in the specification of the system type for SCS.

system SCS

features

power: in feature PhysicalResources::Power;

force: out feature;

properties

ACVIP::Aliases => ("SCS", "Simple Controller");

end SCS;

Some requirements may be for a specific feature of a system, e.g., regarding its input or output. In this case we identify the feature through a for statement in the requirement.

requirement R3 : "SCS inlet voltage" for power [

description "The supplied electrical power shall be 12 volt"

]

We also add the feature as an AADL abstract feature to the component type representing the system (see above). In the end we will have captured all the external interaction points of the system.

When looking at the specification of SCS we may notice that we have an interaction point for incoming electrical power, and for the applied force, but no representation for observations about the state of the controlled system (observed variable).

Often you will need to make adjustments to requirements, typically it is the change of a value rather than the full description of the requirement. We support this by allowing you to specify constants that can then be referenced in the requirement description, a predicate specification, and as parameter to the invocation of a verification.

Constants can be defined at the beginning of the requirement set to be referenced by any requirement in the set, or they can be defined local to a specific requirement.

We also support the definition of global constants. See ReqSpec Technical Report for details.

A constant declaration consists of the keyword val, optionally a type, and the desired value. Numeric values can have measurement units. Any of the unit literals defined by an AADL units property type can be used.

The description can consists of a sequence of strings, referenced to constants, and the keyword this. this acts as placeholder for the name of the model element the requirement applies to.

The requirement R2 rewritten as parameterized requirement.

requirement R2 : "SCS sensor to actuator response time limit" [

val MaximumLatency = 20 ms

description this " shall have a sensor to actuator response time within " MaximumLatency

see goal SCSgoals.g1

]

ReqSpec offers a way of categorizing requirements. Categories are the requirement Kind, Quality attribute, development Phase. The categories can be used to specify filters for viewing, verifying, and reporting on subsets of requirements.

Users can indicate whether a requirement is actually a requirement on the consistency between the requirement specification and the AADL model or of the AADL model (Kind.Consistency). In our example, we have a consistency requirement that all ports of leaf components in an AADL model must be connected.

requirement Allconnected : "All features of all components are connected"[

description "All features of leaf components are connected."

category Kind.Consistency

development stakeholder sei.phf

]

Note that in this example, we have specified a development stakeholder for the requirement. This requirement did not come from a stakeholder of the system as product, but from the development team and we want to track that as well.

Other requirement kinds are constraints on the implementation (Kind.Constraint), assumptions about input or use of resources (Kind.Assumption), and guarantees about output made to users of the system (Kind.Guarantee).

We can also categorize requirements according to quality attributes they represent. The example below represents a latency requirement.

requirement R2 : "SCS sensor to actuator response time limit" [

val MaximumLatency = 20 ms

description this " shall have a sensor to actuator response time within " MaximumLatency

category Quality.Latency

see goal SCSgoals.g1

]

Users can introduce their own categories or extend existing categories with additional labels. They are defined in files with the extension cat. See ReqSpec Technical Report for details.

Each component classifier (type or implementation) can have its own requirement set. All the requirements of the type as well as the implementation apply when we verify a particular component implementation.

In AADL a component type can be an extension of another component type. In this case both the original component type and the extension can have a requirement set, and the requirement set of the original applies to the extension.

In our example, we have an extension of the SCS that operates with two redundant external power supplies.

system SCSDualPower extends SCS

features

backuppower: in feature PhysicalResources::Power;

end SCSDualPower;

This extension has additional requirements to indicate that we expect two external power supplies that are redundant. They are constraints on the specification of SCS, i.e., on the component type of the dual redundant SCS (see DualSCS.reqspe).

system requirements DualSCSreqs for SimpleControlSystem::SCSDualPower [

requirement SR1: "dual power operation" [

description this " shall operate with two external power supplies"

rationale "One power supply acts as backup to the other power supply."

category Kind.Constraint

see goal SCSgoals.ng1

]

requirement SR1_1: "Two power inlets" [

refines SR1

description this " shall provide two power inlets"

rationale "One power supply acts as backup to the other power supply."

category Kind.Constraint

]

requirement SR1_2: "Same voltage" [

refines SR1

description "Both inlets shall operate with the same voltage"

category Kind.Constraint

]

requirement SR1_3: "Same wattage" [

refines SR1

description "Both inlets shall operate with the same wattage"

category Kind.Constraint

]

]

We distinguish between different types of derivation relationships between requirements.

First, we recognize requirement refinement. This is the case when a requirement is subdivided into one or more precise or verifiable requirements for the same system. This is expressed by a refines reference to another requirement of the same component, as shown in the previous example for requirements SR1_1, SR1_2, SR1_3.

Second, we recognize requirement decomposition. In this case a requirement for a system determines requirements on subsystems of that system. This is expressed by a decomposes reference to the requirement of the enclosing component. More than one requirement can be referenced. We have two ways of recording such a decomposition.

system requirements SCSImplementationreqs for SimpleControlSystem::SCS.tier0 [

requirement DCS_R1 : "DCS weight limit" for dcs [

val MaximumWeight = 0.6 kg

category Quality.Mass

description this " shall be within weight of " MaximumWeight

decomposes scsreqs.R1

]

Third, a requirement may evolve - expressed by an evolves reference to the requirement it evolved from. One example is when the requirement evolves over time with a change in text or in its constant value. In this case the original requirement may be tagged as dropped. Another example is when a component type that extends another component type changes a requirement of the original component type, e.g., the constant value. In this case, the requirement associated with the extension sets a new val value.

Some requirements are not for a specific system, but should be applied to a system and all its components, or to different systems. An example are consistency requirements on the AADL model such as the one mentioned earlier about all ports being connected.

Users can define such reusable requirements as global requirement sets in a separate file with the reqspec extension. In the example below (found in file globalreq.reqspec), we show two variants of the requirement that all port are to be connected.

global requirements globalReq

[

requirement connected : "All features of a component are connected"[

description "All features of a component are connected."

when alisa_consistency.ModelConditions.isLeafComponent()

category Kind.Consistency

development stakeholder sei.phf

]

requirement Allconnected : "All features of all components are connected"[

description "All features of leaf components are connected."

category Kind.Consistency

development stakeholder sei.phf

]

]

The first requirement is specified as a conditional requirement to indicate that it applies only for leaf components, i.e., components without subcomponents. In this case, when we add this reusable requirement to the requirement set of SCS (see the include statement below) the requirement gets attached to each leaf component of the AADL instance model whose root system implementation is identified by the assurance plan.

Note: The condition is encoded in a Java method that is referenced by the when statement. In our example we have written the condition method in a separate Java class ModelConditions, found in the Alisa-Consistency project. See below on writing Java based verification methods.

include globalReq.connected

The second requirement is specified for the system as a whole. In this case it is associated with the top level system and the verification activity will traverse the model and verify each leaf component. The key words for self indicate that the requirement is only applied to the target component itself.

include globalReq.Allconnected for self

The difference between the two is that in the first case there is a separate requirement with the verification result as evidence record in the assurance case instance for each component , while in the second case the requirement is recorded only for the top level system with the verification producing a report detailing any leaf component that does not satisfy the requirement. In other words, in the first case, the verification activity only examines the component that is the target of the verification, while in the second case the verification activity traverses the AADL instance model to find and verify each leaf component.

In the next section we will show you how such verification methods are written, registered, and used in verification plans.

System requirements are expected to be verified. This is accomplished by defining a verification plan for each of the system requirement sets. A verification plan consists of a claim for each of the requirements. The claim consists of a set of verification activities, and an optional logical expression (assure clause) to represent the argument for meeting the claim. By default all verification activities must be met. Otherwise, users can express conditional relations between verification activities, e.g., one must be successful before a second one is performed, or a second verification activity is the backup in case the first does not succeed. For the full set of logic expressions see the online help for ALISA in OSATE.

In the example below (found in file scsvplan.verify) the first claim consists of two verification activities to verify the weight requirement. Both will be executed when the system is being verified. The first verification activity invokes an OSATE analysis plug-in, while the second invokes a Resolute claim function. The second claim also consists of two verification activities. In this case, the latency analysis is performed on the assumption that the system is schedulable. Therefore, we specify that the timing activity must complete successfully before the latency analysis is performed.

Note: The call to the verification method does not explicitly specify the component instance on which the verification is performed. It is automatically supplied to the Plugin method or Resolute method as first parameter.

verification plan scsvplan for scsreqs

[

claim R1 [

activities

actualsystemweight : Plugins.MassAnalysis()

[ category Quality.Mass ]

MaxWeight : Resolute.verifySCSReq1(MaximumWeight in kg) [ category Quality.Mass ]

]

claim R2 [

activities

responsetime : Plugins.FlowLatencyAnalysis()

timing: Plugins.ResourceAllocationScheduling()

assert timing then responsetime

]

Verification activities are performed on AADL instance models. The AADL models themselves may be verified, or the verification may be invoked on an artifact referenced by the AADL model, e.g., a Simulink model of a detailed design, or actual source code associated with a thread.

Verification activities invoke verification methods. Method registries identify the methods available to the user. The verification results are tracked in the ALISA assurance case instance (file with the assure extension and displayed as assurance result).

One set of verification methods are the analysis plugins of OSATE. Their registry is called Plugins. The analysis plugin is called with the system instance (instance model root) as its parameter. OSATE analysis plugins report their results through the Eclipse Marker mechanism - they are mapped into a set of result issues in the ALISA assurance case (Assure file).

Note that we may have several latency requirements. In this case the latency analysis plugin is called only once, and the result for each end to end flow requirement is retrieved from the Eclipse markers.

Users can write verification methods in Resolute by defining Resolute claim functions, in Java methods, JUnit test suites, and Agree verifications.

Resolute verification methods are written as claim functions. These claim functions are automatically invoked on the component instance for which the requirement being verified applies. In other words, users do not have to include Resolute annex subclauses with prove statements into the AADL model. Instead the Resolute claim function (registered as verification method) is called on every component instance that has a requirement with a verification activity that calls the registered verification method. An example verification activity calling a registered Resolute verification method.

MaxWeight : Resolute.verifySCSReq1(MaximumWeight in kg)

The claim function is assumed to have at least one parameter, the component instance that is automatically passed as first parameter. The Resolute claim function may take additional parameters.

The Resolute claim function is defined in a Resolute annex library. Our example function is defined as follows:

SCSReq1(self : component, max :real) <=

** "R1: SCS shall be no heavier than " max%kg **

AssureSubcomponentTotals(self, max) and

AssureRecursivetotals(self, max)

In the above example we have specified that the value is to be converted into kg before being passed in the call. The parameter value is a reference to a constant value defined as part of the requirement being verified (see requirement R1 of SCS earlier).

The verification method registry entry - declared in a file with the extension methodregistry is as follows:

verification methods Resolute [

method verifySCSReq1 (max: real ): "Verify SCS weight is within specified maximum (Req1)" [

resolute SCSReq1

description "SCS has a requirement not to exceed a specified weight of 'max' kg. This is verified by summing gross weights of direct subcomponents and by adding up gross weights all parts."

validation validateWeightBudgetCoveragePercent()

]

The method defines the formal parameters (other than the default first parameter) to be used in the call by a verification activity (in our example a real value). It then identifies the Resolute claim function by name.

Following Resolute conventions for Resolute prove statements claim functions do not have to be qualified by a Resolute library name.

The method specification in our example includes a validation call. The specified method is called to determine the validity of the verification result. Here we assess whether all components with a weight actually had a weight related property.

Any issue identified by the validation is included in the assurance case result, e.g., that 70% of components had weight assigned.

Resolute claim functions report successful (pass) or unsuccessful fail) execution of a predicate. In case of fail a specific fail message may be added through a resolute fail statement (see Resolute documentation). The Resolute results are mapped into the ALISA assurance case instance (Assure file).

A Resolute claim function may call other Resolute claim functions. The results are reported back as nested pass or fail results.

NOTE: Resolute claim functions may query the AADL instance model for all threads, processes, or all component instances and then invoke a claim function on each element. In this case Resolute tracks the application of the actual verification in each element as a Resolute (sub-)result. Again all nested Resolute results are mapped back into the ALISA assurance case instance.

Users can also write verification methods in Java. You do this by creating a Plugin project. In out example Alisa-Consistency is such a project. You define dependencies on plugins from OSATE in MANIFEST.INF to have access to utility methods for operating on AADL models.

Java methods can be written as static methods or non-static methods.

Methods can be written for verifying component instances, or for instances of elements inside components, i.e., feature instances, flow spec or end to end flow instances, connection instances. The expected instance model element is defined as first parameter with the appropriate Java class from the AADL instance Meta model, i.e., FeatureInstance, FlowSpecificationInstance, EndToEndFlowInstance, ConnectionInstance.

Note: Instance model elements other than component instance are useful for requirements that are specified for component elements via the for statement of the requirement.

Java verification methods are expected to return true if the requirement is met (Pass) and false if not (Fail). They may also throw an AssertionError exception to indicate an unsuccessful evaluation of a condition (Fail). Exceptions of any other kind are interpreted as the method failing to complete execution, i.e., an Error.

The following example method operates on a Feature Instance, retrieves the property value for voltage and compares it against the value supplied as second parameter.

public static boolean hasVoltage(FeatureInstance fi, double v) {

double volt = getVoltage(fi);

return volt == v;

}

The helper method getVoltage is defined as follows.

Note that for predefined properties utility methods for retrieving property values exist in the class GetProperties. A second class PropertyUtils provides additional support methods.

public static double getVoltage(final FeatureInstance fi) {

Property voltage = GetProperties.lookupPropertyDefinition(fi, "Physical", "Voltage");

UnitLiteral volts = GetProperties.findUnitLiteral(voltage, "V");

return PropertyUtils.getScaledNumberValue(fi, voltage, volts, 0.0);

}

The registry entry for this method takes on the following form - indicating that the method will return a boolean to report Pass or Fail.

method ConsistentVoltage (feature, voltage: real ) boolean

:"Ensure Voltage property value is consistent with required voltage value" [

java alisa_consistency.ModelVerifications.hasVoltage(String name, double voltage)

description "Verify that the Voltage property has the same value as specified in the requirement"

]

This method is then called in a verification activity as follows specifying only the second Java method parameter.

hasvoltage: Alisa_Consistency.ConsistentVoltage(volts)

The requirement identifies the model element power.

requirement R3 : "SCS inlet voltage" for power [

val volts = 12.0 //V

compute actualvolt: real //Physical::Voltage_Type

value predicate volts == actualvolt

see goal SCSgoals.g3

]

The next example illustrates how such a verification can be performed when the target element is the component instance. In this case the feature name is passed in as additional parameter. In the method we search for the feature instance that matches the name and then retrieve the property value and compare it.

Such a method is useful if the requirement was written without identifying the feature with a for statement. Such a method is most useful to write in Resolute as Resolute claim functions can only be called on component instances.

public static boolean hasWattage(ComponentInstance ci, String featurename, double w) {

for (FeatureInstance fi : ci.getAllFeatureInstances(FeatureCategory.ABSTRACT_FEATURE)) {

if (fi.getName().equalsIgnoreCase(featurename)) {

double watt = GetProperties.getPowerBudget(fi, 0.0);

return watt == w;

}

}

return false;

}

Some Java verification methods may evaluate conditions on multiple model elements. In this case we want to report back all model elements that do not meet the condition. In our example, we check that all leaf components have all their features connected and we want to report any unconnected feature.

We first create a ResultReport object, which will collect any issues to be reported. We then traverse the instance model starting with the component instance to which the verification activity applies. When we encounter a leaf component instance, i.e., one without sub component instances, we check that all its feature instances have incoming or outgoing connections. If we encounter one without connections we report this as an Fail issue.

public static ResultReport allComponentFeaturesConnected (ComponentInstance ci) {

ResultReport report = ResultsUtilExtension.createReport("AllFeaturesConnected", ci);

for (ComponentInstance subi : ci.getAllComponentInstances()) {

if (isLeafComponent(subi)) {

for (FeatureInstance fi : subi.getAllFeatureInstances()) {

if (!isConnected(fi)) {

ResultsUtilExtension.addFail(report.getIssues(),

"Feature " + fi.getName() + " of component "

+ fi.getContainingComponentInstance().getName() + " not connected",

fi, "AllFeatureConnected");

}

}

}

}

return report;

}

public static boolean isConnected(FeatureInstance fi) {

return !(fi.getSrcConnectionInstances().isEmpty() &&

fi.getDstConnectionInstances().isEmpty());

}

This Java method is registered as follows - indicating the return value is a report.

method AllComponentsConnected()report: "Check that all features of all leaf components are connected" [

java alisa_consistency.ModelVerifications.allComponentFeaturesConnected

description "Check that all features of all leaf components are connected."

]

Users can specify value predicates as part of a requirement specification.

This predicate can specify a condition involving ReqSpec constants and property values in the model. This predicate is evaluated once for the requirement.

This allows us to specify a condition that the requirement constant val value is the same as the value of a property. Here is an example:

requirement R1 : "SCS weight limit" [ val MaximumWeight = 1.2 kg compute actualweight: real units SEI::WeightUnits category Quality.Mass description this " shall be within weight of " MaximumWeight // verify that MaximumWeight is same as the property value WeightLimit value predicate MaximumWeight == #SEI::WeightLimit see goal SCSgoals.ng2 ]

This predicate can also include compute variables. Compute variables are unbound variables, whose values are bound as result of executing a compute function that is called in a verification activity.

The second form allows us to specify the predicate condition once as part of the requirement without having to implement the predicate condition in each of the verification methods being called in verification activities.

The following is a requirement that specifies an unbound compute variable called actualvolt. It is compared in the value predicate against the specified volts.

requirement R3 : "SCS inlet voltage" for power [

val volts = 12.0 V

compute actualvolt: Physical::Voltage_Type

value predicate volts == actualvolt

see goal SCSgoals.g3

]

In the claim for this requirement (below) the second verification activity calls a compute function that returns a real value that gets bound to actualvolt. During the execution of the verification activity, the compute function is called and then the predicate is evaluated to determine the Pass/Fail result.

claim R3 [

activities

hasvoltage: Alisa_Consistency.ConsistentVoltage(volts)

consistentvoltage: actualvolt = Alisa_Consistency.GetVoltage()

]

The compute function GetVoltage is registered by indicating that a real value is returned.

The method can return more than one value and each value will be bound to a separate compute variable specified in the call.

method GetVoltage (feature) returns (volts: Physical::Voltage_Type in V )

:"Return the Voltage property value" [

java alisa_consistency.ModelVerifications.getVoltage

description "Retrieve the Voltage property from the feature instance"

]

The Java method implementation looks like this.

public static double getVoltage(final FeatureInstance fi) {

Property voltage = GetProperties.lookupPropertyDefinition(fi, "Physical", "Voltage");

UnitLiteral volts = GetProperties.findUnitLiteral(voltage, "V");

return PropertyUtils.getScaledNumberValue(fi, voltage, volts, 0.0);

}

In some cases the verification method expects the values it operates on to be available as property values in the model. We can specify this fact as part of the verification method registration.

We use the GetVoltage Java method to illustrate this capability. We register a new method SetGetVoltage that will set the property value that is specified as part of a call and then call the GetVoltage Java method to retrieve it. The registration is as follows.

method SetGetVoltage (feature) properties(Physical::Voltage)returns (volts: Physical::Voltage_Type in V )

:"Ensure Voltage property value is consistent with required voltage value" [

java alisa_consistency.ModelVerifications.getVoltage

description "Verify that the Voltage property has the same value as specified in the requirement, and set the property value if not present."

]

Note: We register the getVoltage method from above. The property will be set automatically as part of the verification activity execution. Then the getVoltage method is called and the predicate evaluated.

The call in the verification activity is specified as follows.

matchvoltage: actualvolt = Alisa_Consistency.SetGetVoltage() property values (volts)

Note: The model element must not have a property value for the specified property or the value must be the same as the one specified in the call. If a property value already exists and it differs an Error issue will be reported.

ALISA supports running of JUnit tests as verification activities. This is accomplished by registering a JUnit test class. In our example we have a JUnit test class called testme.

verification methods mymethods [

method testJunit : "Run JUnit4" [

junit junittest.testme

]

]

The primary purpose is to support execution of Java based tests of source code related to the system. JUnit test results are mapped into the ALISA assurance case instance representation. An exmple JUnitb test is shown here.

@Test

public void testingCrunchifyAddition() {

assertEquals("Here is test for Addition Result: ", 30, addition(27, 3));

}

JUnit tests are currently called without parameters. In other words, the test method is not passed a component instance to be verified.