- Table of Contents

- 1. Application Planning and Deliverables

- 1.1. Background

- 1.2. Objectives

- 1.3. Scope

- 1.4. Constraints

- 1.5. Assumptions

- 1.6. Risks

- 1.7. Deliverables

- 2. Design and Architecture

- 2.1. Concepts

- 2.1.1. CVEs

- 2.1.2. CPEs

- 2.1.3. cvechecker

- 2.2. Logical Approach

- 2.2.1. Get CVE and CPE data

- 2.2.2. Get version detection rules

- 2.2.3. Scan files for CPE data

- 2.2.4. Read watchlist CPE data

- 2.2.5. Store CVE and CPE data

- 2.2.6. Store version detection rules

- 2.2.7. Store CPE data

- 2.2.8. Report potential vulnerabilities

- 2.2.9. Report installed / watched software

cvechecker design and architecture

Sven Vermeulen 2011/04/141. Application Planning and Deliverables

|

This document is work-in-progress! |

Applications tend to grow and grow as they evolve. To ensure that the application stays within the boundaries of its early thoughts, proper design and planning is often touted to be the key to success. Although cvechecker isn't developed by a large company with architects, analysts, designers and programmers in place, I find that it is still best to have such a design document available - if not alone just to inform potential co-developers on how everything fits together.

I'm going to start with the BOSCARD information on the applications' planning and then continue with the design.

1.1. Background

cvechecker started to form when I noticed that more and more applications are being created based on popular free software components, ranging from small development libraries to enterprise-grade application servers and messaging systems. By itself, I applaud all use of free software - but when you make it part of another product, you must make sure that the evolutions in that component are considered with it. And that's where some vendors or users fail - they tend to include whatever version works for their product, but don't consider potential security vulnerabilities.

More than often do I notice applications that use vulnerable or even unsupported components (in which the community puts no effort in anymore). When we, at my employer, ask the vendor how riskfull he finds a particular security vulnerability that was open in the wild for a component/version he used, we more than often hear that they will update the component. But tracking components and their vulnerabilities is not our primary focus, so I thought "why not create an application or process that does it for me"?

There the idea of cvechecker was born.

1.2. Objectives

The objectives of cvechecker are:

-

Be able to, given a set of files, deduce the components (with versions) that are offering these files

For instance, a file called libbz2.so should result in the necessary identification of bzip2, version 1.0.5

-

Be able to, given a deduced component, identify potential vulnerabilities by using freely available security vulnerability information

For instance, given bzip2 version 1.0.5, report that CVE-2010-0405 might describe a potential threat

Since the start of the cvechecker project, the following objectives have been added

-

Be able to, given a particular system, report on the components (with versions) found on the system

-

Be able to, given a described component (without requiring cvechecker to actually deduce it from a file), identify potential vulnerabilities by using freely avaialble security vulnerability information

For instance, give cvechecker "bzip2 version 1.0.5" and have it report that CVE-2010-0405 might describe a potential threat

1.3. Scope

The cvechecker application's current scope is to run successfully on Linux platforms, but be sufficiently platform independent to support other Unix systems. Support for the Windows platform is not in scope (but if anyone wants to take a stab or give me some pointers on how to create such platform-independent software it would be greatly appreciated).

Automated detection of software based on a heuristic approach is not in scope (in other words, software detection should always be linked with a user-defined metric, setting or expression). This is primarily to keep the scope fixed and the tools' complexity low.

The scans that cvechecker will do will be local - remotely scanning targets is not in scope.

1.4. Constraints

As I'm running free software only on my system, I can only add the necessary support for the free software components that I am running. Although I tend to have many services running in virtual environments, feedback on detection rules (cfr. the user guide documentation) is greatly appreciated.

1.5. Assumptions

The design of the tool assumes that the version of a software component is more than often hardcoded within, allowing simple expressions to extract the version from these files. This can be easily confirmed with most command-line tools:

~$ cat --version cat (GNU coreutils) 8.7 Packaged by Gentoo (8.7 (p1)) Copyright (C) 2010 Free Software Foundation, Inc. ... ~$ strings -n 3 /bin/cat | grep 8.7 8.7 8.7 (p1)

1.6. Risks

If more and more applications do not hardcode their version in such a way that it can be easily retrieved from the file content, the method used by cvechecker will fail to deliver results. To mitigate the risk, the tool already supports the notion of "version gathering routines" so that, if necessary, additional methods can be added.

On hardened systems, not all binaries and libraries can be read. Although this is merely a matter of adjusting the security policy, this does pose a potential security problem. To mitigate the risk, the tool now also supports partial functionality (i.e. reporting) based on given information (rather than deduced).

1.7. Deliverables

Besides the objectives given earlier, the following are additional requirements / deliverables:

-

Reporting should be based on CSV information (Comma Separated Values), allowing for other applications to easily work with the provided information.

2. Design and Architecture

2.1. Concepts

2.1.1. CVEs

CVEs (Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures) are a market standard approach for documenting vulnerabilities and threats within software, hardware and operating systems. A CVE has a syntax of

CVE-<year>-<sequence>, such as CVE-2010-0405. CVEs are publicly disclosed. One source of CVE information are the feeds of nvd.nist.gov.

2.1.2. CPEs

CPEs (Common Platform Enumeration) is a identification syntax to identify hardware, software or operating systems. It has a syntax of

cpe:/<type>:<vendor>:<product>:<version>:<update>:<edition>:<language>. such as "cpe:/a:bzip:bzip2:1.0.6:::.

CVEs report which CPEs are affected by their content. Although the CPE syntax is well known and documented, not all CPEs are correctly filled in or their syntax changes as acquisitions occur. A notable example is java, which was earlier known as "cpe:/a:sun:java:jre:6:update_1::" and then as "cpe:/a:oracle:jre:6:update_19". Users of CPEs should definitely take such changes into account.

2.1.3. cvechecker

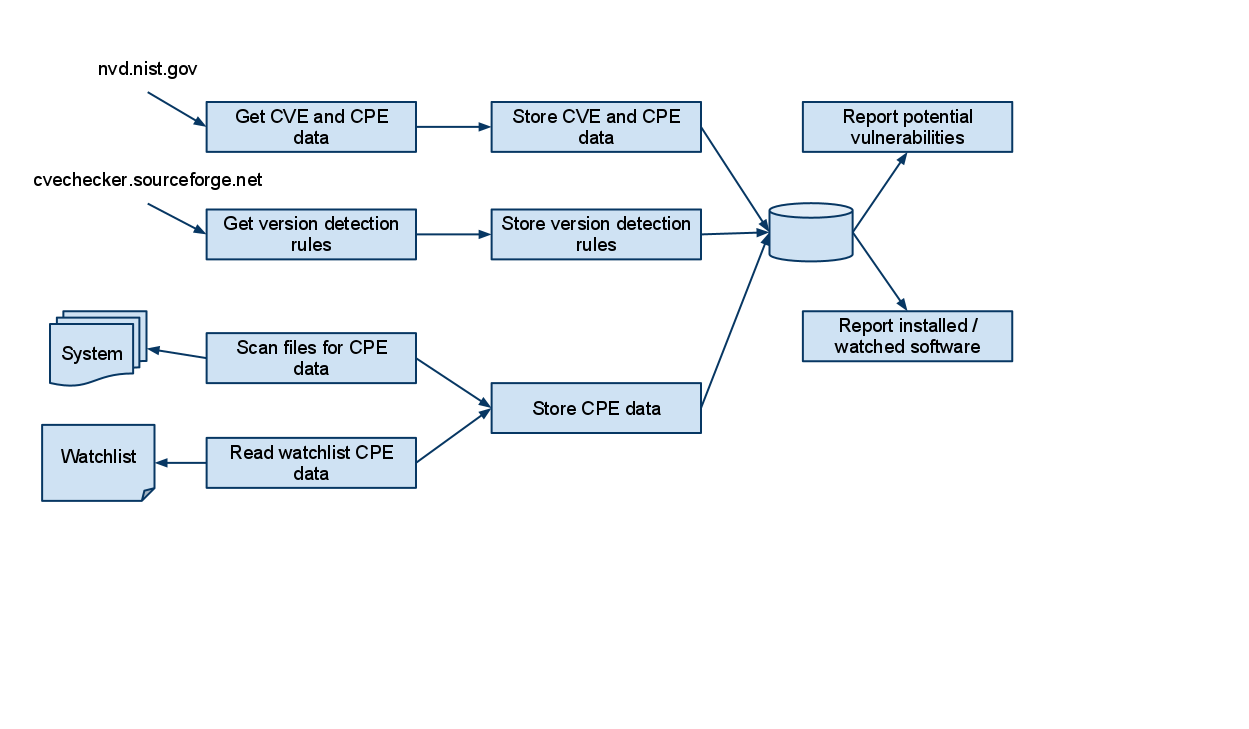

The following diagram gives a conceptual overview of the application.

-

"Get CVE and CPE data" retrieves the publicly available CVE information (with the included CPE information)

-

"Get version detection rules" retrieves the version detection rules as delivered by the cvechecker project

-

"Scan files for CPE data" scans the system (given a set of files to scan on the system) for software

-

"Read watchlist CPE data" retrieves CPE information from a watchlist file as delivered by the user

-

"Store CVE and CPE data" stores the CVE and CPE data retrieved from "Get CVE and CPE data" in the database

-

"Store version detection rules" stores the version detection rules as received by "Get version detection rules" in the database

-

"Store CPE data" stores the CPE information as received from "Scan files for CPE data" and "Read watchlist CPE data" in the database

-

"Report potential vulnerabilities" queries the database for any match of CPE information (received from the "Store CPE data") with CVE information (received from the "Store CVE and CPE information")

-

"Report installed / watched software" queries the database for the information stored by "Store CPE data"

Given the tool's deliverables, the reporting blocks need to be able to put the data in CSV format.

2.2. Logical Approach

The design of the abovementioned specific blocks is handled in the next few sections...

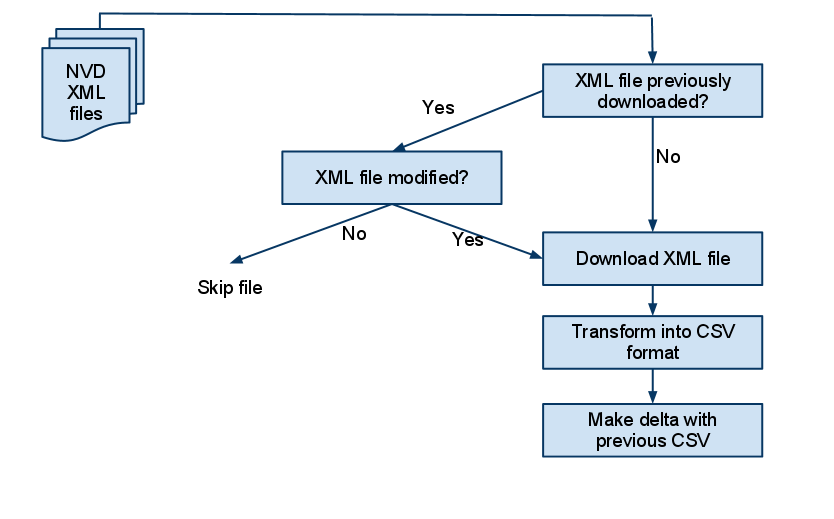

2.2.1. Get CVE and CPE data

As the tool bases itself (currently) on CVE information, we want to retrieve the information as made available by sites such as nvd.nist.gov. This site offers the data in XML feeds:

-

nvdcve-2.0-2002.xml - All CVE information of 2002 and earlier

-

nvdcve-2.0-2003.xml - All CVE information of 2003

-

...

-

nvdcve-2.0-2011.xml - All CVE information of 2011

-

nvdcve-2.0-modified.xml - Recently modified/added CVE information

-

nvdcve-2.0-recent.xml - Recently added CVE information

With this in place, cvechecker pulls in all the year XML files (2002, 2003, ..., 2011) and the modified.xml file. The year-specific files are then not redownloaded anymore as they either don't change, or the changes are also available in the modified.xml file.

The downloaded XML file is then converted in CSV format which contains the CVE+CPE (one set per line) to make it easier for the application to read it. The XML file itself contains lots of other information as well, but that information is irrelevant for this project.

Finally, the CSV file is compared with the previous CSV file (in case the XML file was redownloaded) and the delta itself is stored. This allows the application to only grab the changes rather than having to revisit the entire CVE download (whose processing is quite time consuming).